Rewriting the Stolen Stories of the Graham and Shipp Families

August 18, 2022

This blog was written by Sydney Carroll, archivist of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

*sensitive content warning*

“You’ve found answers in four days that I couldn’t find in forty years. You did more than research...you found my family. We gave them back the stories that were stolen from them.”

Hidden inside the census, slave schedules, deeds, and vital records, Kevin Graham finally learned where he came from. It was not as simple to trace his lineage as one would think, given the intentional erasure of Black names in American historical records.

Kevin called the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room to find answers he had been searching for over the past 40 years. He hoped to link his maternal third great grandfather, Wesley Shipp (1817-1875), to white plantation owner, Bartlett Shipp (1786-1869). Kevin believed that Wesley (or possibly Wesley’s parents) was the first Black Shipp but could not find the records to prove it.

He also wanted to link his paternal great grandfather, George Graham (1840-c1910), and great grandmother, Violet Luckey Graham (1840-c1910), to Elmwood Plantation. Both the Shipp and Graham families (Black and white) have roots in Lincoln County, North Carolina.

To put it simply, Black genealogy is a beast. It is not only difficult to conduct genealogical research due to the lack of historical records for Black Americans, but it is also an emotional road to travel. Many times, the traumatic reminder of slavery is woven into their DNA, resulting in more questions than answers.

With the assistance of Sydney Carroll, archivist of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Kevin said that together we “made cracks in the brick wall” he hit after decades of searching for answers. Laughing, he described his ancestry as a “family bush” instead of a family tree because his lineage is wider than it is tall. After all that time and trauma, it would be understandable to hold some anger and resentment. But Kevin explained that, “There’s no hard feelings. I just want to know.”

WESLEY SHIPP | The First Black Shipp?

Accidental Discoveries

Kevin first inquired if his third great-grandfather, Wesley, was the first Black Shipp. In the initial stages of researching the Shipp line, we did not find concrete, historical evidence to support this theory. However, while conducting historical property research on Wesley's white enslaver, Bartlett Shipp, we “accidentally” discovered a deed dated April 10, 1852, that specifically named Wesley, his wife, Winnie Abernathy Shipp (1820-1905), and five of their children for sale to pay off his debts to his father-in-law, Peter Forney (1756-1834). [1]

Lincoln County, North Carolina Register of Deeds, Deed Book 42:204

It is unclear when Bartlett Shipp first enslaved Wesley, but census records and deeds indicate that it could have been as early as 1822 after purchasing 249.5 acres of land from Peter Forney to build his estate, The Home Place. [2] At this time, Wesley would only be about five years old, so it is possible that Bartlett’s intention was to enslave his mother and/or father and bought Wesley along with them. It is also possible that Bartlett purchased Wesley later in life as a young adult.

Bartlett was born in 1786 in Stokes County but moved to Lincoln County to study law under Joseph Wilson, making him the first Shipp in Lincoln County. These discoveries lead us to believe that Wesley or his mother/father were the first Black Shipps.

Winnie Abernathy Shipp (1820-1905). Courtesy of Ancestry.com

We are still unsure when Winnie, Wesley’s wife, became enslaved at the Shipp plantation. It is possible that the Abernathy family first enslaved Winnie since her son’s death certificate listed “Abernathy” as her maiden name.

Death Certificate for Joe Shipp, June 29, 1928. [3]

Several public family trees on Ancestry list Turner Abernathy (1763-1845), a white farmer, as her father, but no documentation exists to prove it. Turner married Susannah Marie Forney (1767-1850) in 1784, so it is also possible that the Forney family enslaved Winnie and/or her mother, and later sold her to Turner. Or, Turner enslaved Winnie’s mother, whom he raped and impregnated, resulting in the birth of Winnie. This theory would explain why Winnie and her children are described as “mulatto” in the 1870 census. Enumerators assigned “mulatto” to individuals who had mixed Black and white ancestry, a result of the horrendous acts against enslaved Black women by their enslavers.

Clues in the Census

Census records that predate 1850 only include the head of household’s name and the number of people ("free white,” “free colored,” or “slave”) living in the household. Similarly, “slave schedules” recorded enslaved individuals separately during the 1850 and 1860 census. Most schedules do not record the enslaved person’s name, but include information relating to their age, gender, and “color.” Below is a general outline of the 1830-1860 census records for Bartlett Shipp:

- 1830 census-1 male aged 10-23 (Wesley, age 13); 4 females aged 10-23 (Winnie, age 10) [4]

- 1840 census-7 males aged 10-23 (Wesley, age 23); 6 females aged 10-23 (Winnie, age 20) [5]

- 1850 slave schedule-1 male aged 33; closest female is aged 26 [6]

- 1860 slave schedule-0 male aged 43; 0 female aged 40* [7]

*According to the deed, Bartlett Shipp sold Wesley, Winnie, and their five children in 1852, so this data verifies that they were no longer enslaved by Bartlett in 1860.

Unfortunately, early census records require genealogists to infer as to whether the person of interest is included in the stated age range or not. Because of the deed that mentions Wesley and Winnie by name, we have definitive evidence of their enslavement by Bartlett Shipp in 1852.

Wesley, Winnie, and their children in the 1870 Census [8]

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that “all persons held as slaves [in the rebellious states] are, and henceforth shall be free.” [9]

Wesley appears as a “free” man in the 1870 census with Winnie and nine of their children. They lived in Catawba Springs Township, which is about 14 miles from where the Shipp plantation once existed. No other Black Shipp families lived nearby until the 1900 census, when we saw Winnie’s son, William Shipp, and granddaughters, Mary and Agnes Caldwell, living with her in the house she owned.

Life On The Home Place

Rural Delivery Routes Map, Lincoln County, North Carolina, 1851. [10]

Wesley, Winnie, and their children were enslaved on the Shipp plantation, known to the family and community as “The Home Place.” [11] In August 1822, Bartlett purchased 249.5 acres of land from his father-in-law, Peter Forney, for $1,000 (area circled in red). [12] There is evidence that this is the same land that Bartlett built The Home Place, but there is no definitive evidence due to long lost boundary descriptions written into the deed, such as “the fish trap.” [13]

Wesley's family likely farmed cotton at The Home Place, but the Lincoln Courier also suggested that the land had “a quantity of gold, as well as iron.” [14]

“I wanted to know that all of my ancestors made a difference,” Kevin explained. “It strengthens me to know what my ancestors went through. Someone had to survive the boat ride, stay chained up, not risk their life running. My people had to survive Jim Crow, redlining, and the Civil Rights Movement. If they didn’t, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”

GEORGE AND VIOLET GRAHAM | Life at Elmwood Plantation

“I saw George on Zennie’s death certificate. My grandfather was born in 1876, so it wasn’t a reach to think that [his father] could have been enslaved...I googled “Graham Plantation,” which is when I learned about Elmwood Plantation.”

In addition to researching his maternal line, Kevin also asked for help in linking his great grandfather, George Graham, on his paternal line to Elmwood Plantation. White plantation owner John Davidson Graham (1789-1847) built the Graham House, also known as Riverview, between 1825-1828 with the use of forced labor of those he enslaved. [15] Elmwood Plantation sat on 1,200 acres of land near the end of present-day Ranger Island Road in Lincoln County. [16]

We began our research by reading John Davidson Graham’s will dated 1847, where we found George listed by name on the second page. John bequeathed George to his son, Robert Clay Graham. At that time, George was 7-10 years old.

The 1870 census was the first census that recorded the formerly enslaved as people instead of property. In this census, George is listed as a farm laborer married to Violet Luckey Graham, with whom he shared a 3-year-old daughter named Lizzie.

"The success of Elmwood made the plantation owners prideful and boastful, which gave them the desire to preserve historical documentation to cement their legacy. Thus, it has given me a small glimpse into mine, and for that reason I am thankful and blessed.”

The 1900 census states they had been married for 38 years. [17] This means that George and Violet were married in 1862, three years before slavery’s end was enforceable by Union troops in the south. This ties Violet to the Graham family through her marriage to George while he was still enslaved by Robert Clay Graham. [18] If Violet was not enslaved by the Graham family before her marriage to George, the year 1862 is when her (and likely her mother's) connection to Elmwood Plantation began.

On old censuses, enumerators went door to door, so now, present-day researchers can get an idea of neighboring families by looking at who was listed above or below them on the census record. A few rows above George and Violet is Clay Graham--presumably, Robert Clay Graham, son of John Davidson Graham--who is listed as a farmer.

“Because of you I met George, his father, his mother. Violet and her mother. Their children... [Violet and George] are still family names. It matters. The small details matter.”

In Clay's household, a 60-year-old Black woman named Lizzie Luckey was listed as a domestic servant--an interesting coincidence that George and Violet's daughter's name was Lizzie, and that Lizzie's (the older Black woman) last name was Luckey, which matched Violet's maiden name.

The 1880 census shows an Elizabeth Alexander, described as the mother-in-law to the head of the household, living with George, Violet, and their children. [19] This finding confirmed that the Lizzie Luckey on the 1870 census in Clay's household was, in fact, Violet's mother. We believe that Alexander was Lizzie’s maiden name because she was born in Maryland, which is where the well-known Alexander family of Charlotte migrated from in the mid- to late- 18th century.

“I reached the pinnacle. I’m on the mountain top. I am a unicorn. Only 3% of African Americans can trace their lineage back to Africa. I found my way home. I am an American, but now I know the road of how I got here.”

As if he could not be more excited about our findings, we discovered that, according to the 1880 census, George’s father was born in Africa. [20] This is an extremely rare find, as only a small percentage of Black genealogists can trace their lineage directly to Africa.

SHIPP’S LANE AND GRAHAM ROAD | Intersection of Family History

“One of the white Graham descendants wanted to talk to my aunt, but the trauma was still so fresh that she couldn’t. Aunt Zannie worked in the same field that George probably worked in.”

Maps of land surrounding Elmwood Plantation [21] [22]

Shipp’s Lane and Graham Road intersect near the original location of Elmwood Plantation, before Duke Power Company dammed the Catawba River to create Lake Norman. “Grandma Ida lived on Shipp’s Lane and our church was off Graham Road. I connected the two in my head knowing that my people were probably enslaved.” He continued, “It’s amazing that I see Graham Road and it means something to me. I see the name ’Shipp’ with two p’s and it means something to me.”

Bartlett Shipp’s plantation, The Home Place, sat approximately 7 miles away from this intersection, but he and his descendants owned quite a bit of land throughout Lincoln County. “It’s a puzzle that I didn’t even know connected,” Kevin said with disbelief.

“We may have gotten our freedom in 1863, but I grew up going to church down the street from where our enslavers went. So really, I was still on their land.”

Every Sunday morning as a child, Kevin and his family drove past Graham Road on their way to Ebenezer United Methodist Church. Kevin’s father, Zemerie, helped construct the new building, but Kevin recalls the “old white building” and cemetery across the street, where many of his family members are buried.

Ebenezer is located less than one mile from Unity Presbyterian Church, the church that John Davidson Graham and his family attended and are buried at. It is possible that Kevin’s enslaved ancestors also attended Unity, as people who were enslaved were permitted to sit in a designated area in the back pews.

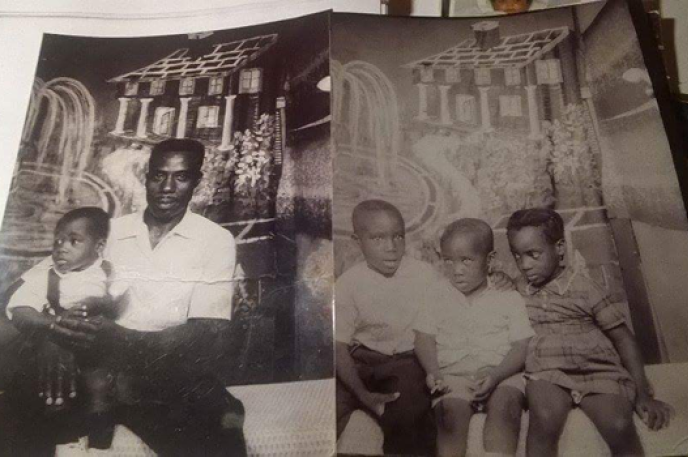

Wendell (brother) and his mother, Vaneva Shipp Graham, at Camp Meeting, c1962

“People say it’s been a long time, but it hasn’t really been much time at all. My father sharecropped. My mother picked cotton. I lived through the modern Civil Rights Movement. I was living and breathing as they were marching. Compared to them, I live my life with no limitations.”

THE GRAHAMS OF TODAY | Living in the Legacy

This We’ll Defend:

Kevin at Fort Jackson during Family Day, c2016

George’s ancestors spent most of their lives defending the country that legally enslaved them just two generations before. Kevin, his older brother, his father, and his five uncles all proudly served in the United States Army. “I served for 27 years, 9 months, and 8 days.” He continued, laughing, “but who’s counting? It was an honor.” Kevin retired from the Army as a Sergeant First Class.

Zemerie Graham, Private First Class, 1942

“My father, Zemerie, achieved [military] awards higher than when I served. At the time, a colored man in the United States Army received awards higher than I received in 27 years of service, but he never got promoted based on color of his skin.”

“My father had different rights as a Black man in America than I have as a Black man in America. My father was better at everything he did. I benefit from the changes he made. My father was so patriotic. The way he loved his country, and I understand why. That’s why I love this country.”

Kevin serving in Tikrit, Iraq, c2005

Kevin continued, “People called my father “Little Soldier,” and he called my brother that too. Our family is known for service. We truly love this country. None of what I’ve learned takes away from that--it actually adds to it. George was a hard worker and had dreams of being free.”

Tucker’s Grove Camp Meeting Ground

Kevin and his family at Camp Meeting, c1967

Left to right: Stephen (brother), Zemerie (father), Wendell (brother), Andreá (sister), and Kevin

Founded in the first half of the 19th century by the Methodist Episcopal Church, Tucker’s Grove Camp Meeting served as a religious site for the spiritual crusade and renewal of the enslaved population. Camp meetings continued “after the abolition of slavery and has been operating continuously since 1876 as an A.M.E. Zion camp meeting site.” [23] Wesley, Winnie, George, and Violet may have attended a camp meeting in their lifetime. We can only wonder if their paths crossed.

“I wanted my daughters to connect with their ancestors. The ground is the same. My people walked on this ground. My people sat on these benches.”

Kevin carries this tradition from his ancestors and passes it down to his daughters. Each August he attends “Big Sunday” with his family for fellowship and worship among the Black Christian community. “[We have] the ability to have conversations about the past. And that means the world to me. You can acknowledge that there is still pain but find that the truth is enriching.”

DNA Testing

“My family left breadcrumbs all over for me to make a connection back home. My life is full of that.”

Ethnicity Estimate breakdown, courtesy of Ancestry.com

“I’ve had three separate strangers think I was Nigerian until they heard me speak. So whatever George had [from his father] is still very present. I still carry it. My ancestors are smiling down on me.” Kevin received the DNA test results above in July 2022, which confirms that those three strangers were right—he does, in fact, have quite a bit of Nigerian DNA.

Ethnicity Estimate map, courtesy of Ancestry.com

All of Kevin's African genes stem from the "Slave Coast” of West Africa, which is common for people who have enslaved ancestors. His DNA Community profile on Ancestry reveals that his ancestors lived in Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas, all confirmed by what we saw on census and vital records.

Interestingly, Kevin has an estimated 13% European ancestry. Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., widely known for his show “Finding Your Roots” on PBS, explains that “...racial purity is one more corroboration that the social categories of ‘white’ and ‘black’ are and always have been more porous than can be imagined, especially in that nether world called slavery.” [24]

Ethnicity Inheritance Chart, courtesy of Ancestry.com

(Red-Ireland; Orange-Sweden and Denmark; Purple-Scotland)

“Well, our DNA proclaims loudly that we are a European people, a multicultural people, a people black as well as white. You might think of us as an Afro-Mulatto people, our genes recombined in that test tube called slavery.” -Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Dr. Gates further explains that “58% of African American people, according to geneticist Mark Shriver at Morehouse College, possess at least 12.5% European ancestry.” [25] This ancestry comes from the result of a white enslaver raping and impregnating a Black female they enslaved—genes that are henceforth passed down from generation to generation.

We saw evidence of this atrocity while researching Winnie Shipp, who was described as “mulatto” along with her children in the 1870 census. The ethnicity inheritance chart above shows that European ancestry exists on Kevin’s paternal line as well.

Final Thoughts | No More Rabbit Holes

“They were living, breathing, loving humans. But back then, slaves were seen as an afterthought. You made them living, breathing, loving humans again. Thank you.”

The Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room policy for reference questions limits staff research time to two hours per patron. Admittedly, I spent more than two hours working with Kevin researching his family history. In fact, he made me promise to not go down any more rabbit holes.

As mentioned before, Black genealogy is a beast. Kevin faced tough questions and even tougher answers. Because of his courage to learn these truths, future generations of his family will now carry a piece of Wesley and Winnie Shipp, and George and Violet Graham with them forevermore.

--

The Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room’s historical and genealogical collections heavily focuses on local and regional materials, providing access to family histories, county and state records, wills, land and vital records, war records, and Ancestry Library Edition. Although Charlotte Mecklenburg Library has access to genealogical databases at every branch, do not hesitate to contact the Carolina Room and speak with our genealogy experts.

--

Citations

[1] Lincoln County, North Carolina Register of Deeds. Deed Book 42:204.

[2] Lincoln County, North Carolina Register of Deeds. Deed Book 42:628.

[3] Ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Deaths, 1906-1930 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

[4] Year: 1830; Census Place: Lincoln, North Carolina; Series: M19; Roll: 122; Page: 206; Family History Library Film: 0018088

[5] Year: 1840; Census Place: Lower Regiment, Lincoln, North Carolina; Roll: 364; Family History Library Film: 0018095

[6] The National Archive in Washington DC; Washington, DC; NARA Microform Publication: M432; Title: Seventh Census Of The United States, 1850; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29

[7] The National Archives in Washington DC; Washington DC, USA; Eighth Census of the United States 1860; Series Number: M653; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29

[8] Year: 1870; Census Place: Catawba Springs, Lincoln, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1146; Page: 136A

[9] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), "The Emancipation Proclamation, NARA, Revised 2022-01-28, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation

[10] United States, Post Office Department. Rural delivery routes, Lincoln County, N.C. [Map]. 1:63,360, Washington, D.C.: Post Office Dept., c1910s. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/ncmaps/id/1799/rec/8

[11] Lincoln County, North Carolina Register of Deeds. Deed Book 49:99-100.

[12] Lincoln County, North Carolina Register of Deeds. Deed Book 42:628.

[13] Foard, Davyd Hood. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Mount Welcome. Prepared January 28, 1991. Accessed July 2022. http://www.lincolncounty.org/DocumentCenter/View/14623/Mount-Welcome?bidId=

[14] "Lincolnton; Thursday, March 30, 1848." Lincoln Courier (Lincoln County, North Carolina), Mar. 30, 1848.

[15] Fortenberry, Ken. “Historic Elmwood Plantation.” Lincoln County North Carolina History Facebook Group, 2010. https://www.facebook.com/750601628308901/photos/historic-elmwood-plantation-2010-by-ken-h-fortenberry-although-some-beautiful-mi/772012112834519/?_rdr

[16] Ibid.

[17] Year: 1870; Census Place: Catawba Springs, Lincoln, North Carolina; Roll: M593_1146; Page: 157B

[18] Year: 1900; Census Place: Catawba Springs, Lincoln, North Carolina; Roll: 1203; Page: 6; Enumeration District: 0105; FHL microfilm: 1241203

[19] Year: 1880; Census Place: Catawba Springs, Lincoln, North Carolina; Roll: 970; Page: 257B; Enumeration District: 100

[20] Ibid.

[21] Burke, R.T. Avon, W. Edward Hearn, and Lonn Leland Brinkley. Soil Map, North Carolina, Lincoln County [map]. 1:62,500. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1914. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/ncmaps/id/297/rec/10

[22] Google Maps, 2022.

[23] Survey and Planning Unity Staff, State Department of Archives and History. National Register of Historic Places, Tucker's Grove Camp Meeting Ground. Prepared Feb. 17, 1972. https://www.lincolncounty.org/DocumentCenter/View/14649/Tuckers-Grove-Camp-Meeting-Ground

[24] Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. "Michelle's Great-Great Great-Grandaddy--and Yours." History News Network. Columbian College of Arts & Sciences, The George Washington University, Published Oct. 8, 2009. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/118292

[25] Ibid.

Bibliography

Davidson College Archive and Special Collections. "Elm Wood (Graham) Plantation." Under Lake Norman. Published 2015. Accessed July 2022. https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/archives/community/under-lkn/elm-wood

Sherrill, William. Annals of Lincoln County North Carolina. Charlotte, NC: The Observer Printing House, Inc., 1937. (NCR 975.61 L56 S55a)

York, Maurice C. Our Enduring Past: A Survey of 235 Years of Life and Architecture in Lincoln County, North Carolina. Lincolnton, NC: Lincoln County Historic Properties Commission, 1986. (NCR 975.61 L56 B87m)

Help Shape the New Sugar Creek Library!

December 5, 2025

Monday, December 8

5:30pm - 7:30pm

Ella B. Scarborough Community Resource Center

430 Stitt Rd, Charlotte, NC 28213

Join us for an interactive community session with the NEW Sugar Creek Library design team.

See the location -- just across the street from the EBS CRC -- of the new Library site! The footprint will be staked, so you can imagine the building coming to life in your neighborhood.

As we enter the last design phase before construction, your ideas and feedback are more important than ever. We will share how community input has guided the design so far and engage you in hands-on activities to shape the final design.

Open to all. Space is limited. Refreshments provided.

If you plan to attend, RSVP here: https://bit.ly/4pNNjaM

Charlotte Mecklenburg Library’s Top Circulated Books of 2025

December 23, 2025

This blog was written by Eric Williams, marketing and communications specialist for Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

Before we close the book on 2025, let's take a look back at what Charlotte Mecklenburg Library customers checked out the most this year beginning with the top circulated title in each genre:

Best in Genre

Fiction

The Women by Kristin Hannah

Non-Fiction

The Let Them Theory by Mel Robbins

Children’s

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Hot Mess by Jeff Kinney

Young Adult

Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne Collins

Romance

Great Big Beautiful Life by Emily Henry

Mystery

The Grey Wolf by Penny Louise

Science Fiction

Onyx Storm by Rebecca Yarros

African American

James: A Novel by Percival Everett

Audiobook

The Women: A Novel by Kristin Hannah

Fiction

The Women by Kristin Hannah

The Wedding People: A Novel by Alison Espach

The God of the Woods by Liz Moore

Nightshade: A Novel by Michael Connelly

All the Colors of the Dark: A Novel by Chris Whitaker

The Frozen River: A Novel by Ariel Lawhon

The Waiting by Michael Connelly

To Die for by David Baldacci

Atmosphere: A Love Story by Taylor Jenkins Reid

My Friends: A Novel by Backman Fredrik

Non-Fiction

The Let Them Theory: A Life-changing Tool That Millions of People Can't Stop Talking About by Mel Robbins

The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt

Be Ready When the Luck Happens: A Memoir by Ina Garten

Atomic Habits by James Clear

Framed: Astonishing True stories of Wrongful Convictions by John Grisham

Original Sin: President Biden's Decline, its cover-up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again by Jake Tapper

Good Energy: The Surprising Connection Between Metabolism and Limitless Health by Casey Means

The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War by Erik Larson

Revenge of the Tipping Point: Overstories, Superspreaders, and the Rise of Social Engineering by Malcolm Gladwell

What to Cook When You Don't Feel Like Cooking by Caroline Chambers

Children’s

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Hot Mess by Jeff Kinney

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Rodrick Rules by Jeff Kinney

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Wrecking Ball by Jeff Kinney

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Third Wheel by Jeff Kinney

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Long Haul by Jeff Kinney

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Getaway by Jeff Kinney

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Last Straw by Jeff Kinney

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Dog Days by Jeff Kinney

Tales from a Not-So-Bratty Little Sister by Rachel Renée Russell

Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Ugly Truth by Jeff Kinney

Young Adult

Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne Collins

A Good Girl's Guide to Murder by Holly Jackson

Wrath of the Triple Goddess by Rick Riordan

Powerless by Lauren Roberts

The Chalice of the Gods by Rick Riordan

The Summer I turned Pretty by Jenny Han

Fearless by Lauren Roberts

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes by Suzanne Collins

To All the Boys I've Loved Before by Jenny Han

Divine Rivals: A Novel by Rebecca Ross

Graphic Novels

Sisters by Raina Telgemeier

Maus: A Survivor's Tale by Art Spiegelman

One piece. Vol. 108, Egghead. Part 3, Better Off Dead in This World by Eiichirō Oda

One piece. Vol. 107, Egghead. Part 2, Hero of Legend by Eiichirō Oda

The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis & J.R.R. Tolkien by John Hendrix

Berserk: Deluxe Edition. 1 by Kentarō Miura

Berserk: Deluxe Edition. 2 by Kentarō Miura

Spy x Family. 1 by Tatsuya Endō

The Odyssey: A Graphic Novel by Gareth Hinds

One-Punch Man. 01 by ONE

Romance

Great Big Beautiful Life by Emily Henry

Say You'll Remember Me by Abby Jimenez

Funny Story by Emily Henry

Just for the Summer by Abby Jimenez

Deep End by Ali Hazelwood

Problematic Summer Romance by Ali Hazelwood

Part of Your World by Abby Jimenez

One Golden Summer by Carley Fortune

The Paradise Problem by Christina Lauren

The Love Haters by Katherine Center

Mystery

The Grey Wolf by Louise Penny

We Solve Murders by Richard Osman

Now or Never: Thirty-One on the Run by Janet Evanovich

Bonded in Death by J. D. Robb

Listen for the Lie: A Novel by Amy Tintera

The Missing Half: A Novel by Ashley Flowers

Marble Hall Murders: A Novel by Anthony Horowitz

Kills Well with Others by Deanna Raybourn

Nobody's Fool by Harlan Coben

Don't Forget Me, Little Bessie: A Novel by James Lee Burke

Science Fiction

Onyx Storm by Rebecca Yarros

Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros

Iron Flame by Rebecca Yarros

The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune

Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil by Victoria Schwab

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Somewhere Beyond the Sea by TJ Klune

Project Hail Mary: A Novel by Andy Weir

Dune by Frank Herbert

Blood Over Bright Haven: A Novel by M. L. Wang

African American Fiction

James: A Novel by Percival Everett

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by James McBride

King of Ashes: A Novel by S. A. Cosby

Good Dirt: A Novel by Charmaine Wilkerson

Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

This Could be Us by Ryan Kennedy

Harlem Rhapsody by Victoria Christopher Murray

All the Sinners Bleed by S. A. Cosby

Can't Get Enough by Kennedy Ryan

A Love Song for Ricki Wilde by Tia Williams

Top Audiobooks

The Women: A Novel (unabridged) by Kristin Hannah

Onyx Storm: (unabridged) by Rebecca Yarros

Great Big Beautiful Life: (unabridged) by Emily Henry

The Wedding People: A Novel (unabridged) by Alison Espach

Just for the Summer: (unabridged) by Abby Jimenez

The Perfect Divorce: (unabridged) by Jeneva Rose

Say You'll Remember Me: (unabridged) by Abby Jimenez

None of This is True: (unabridged) by Lisa Jewell

The Perfect Marriage: (unabridged) by Jeneva Rose

The God of the Woods: A Novel (unabridged) by Liz Moore

Libby by Overdrive Magazines

The New Yorker

US Weekly

New Scientist

The Week Magazine

National Geographic Magazine

Local puppeteer will attempt to make history this Sunday at ImaginOn

January 15, 2026

This blog post was written by Eric Williams, marketing and communications specialist for Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

It is well known among Charlotte Mecklenburg Library users that ImaginOn is where stories come to life; but on this Sunday, 1/18, it will have a special opportunity to help bring history to life as well—and you are invited to be a part of it! Cheralyn Lambeth is a local, experienced puppeteer and educator with a unique twist: she is a Guiness World Record holder for the largest collection of finger puppets. She earned the title in 2022 and as of 2025 she has over 2500 finger puppets in her collection!

Now, she will attempt to reclaim her title at the one and only ImaginOn! If you find yourself in the area, visiting ImaginOn, or attending a show at the Children’s Theatre of Charlotte, we encourage you to come watch and cheer Cheralyn on as an official count will commence at 1:30pm.

Something also worth mentioning is that this event will be held just a couple of weeks prior to PuppetPalooza, ImaginOn’s free annual puppetry festival, taking place on Saturday January 31 from 10am – 4:30pm. Cheralyn will be one among several amazing puppeteers and puppetry troupes who will be performing and participating in PuppetPalooza.

For more information on the Cheralyn’s World Record attempt and PuppetPalooza, please visit this link. We hope to see you there!

Mountain Island Library Reopens January 20

January 18, 2026

Since November, the Mountain Island branch has been closed for renovations and facility maintenance. The work is now complete, and the library will reopen on Tuesday, January 20. Customers can look forward to updated lighting in the branch, HVAC and other mechanical systems functioning properly, as well as the reopening of the library's bookdrop. Mountain Island staff look forward to welcoming customers back to the branch. Customers can also view and register for upcoming programs and events at Mountain Island Library here.