How July 2 almost became Independence Day

July 2, 2019

Yes, you read that right!

The legal separation of the Thirteen Colonies from Great Britain in 1776 actually occurred on July 2, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence proposed by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. Lee made three main points, to include a declaration of independence, a call to form foreign alliances and a “plan for confederation”:

Lee’s Resolution, June 7, 1776 (National Archives and Records Administration: 301685 )

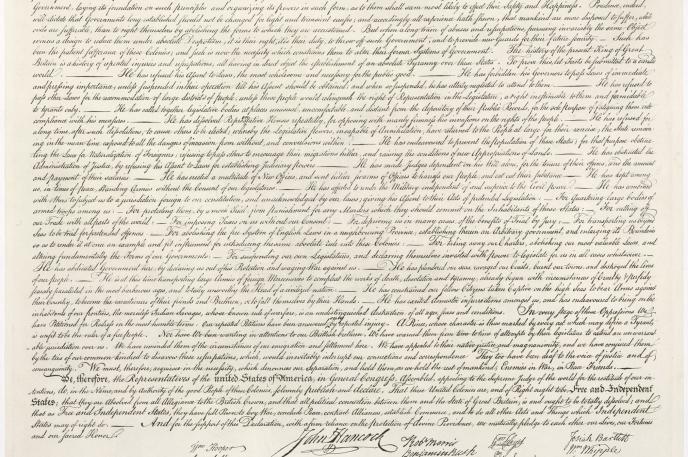

After approving Lee’s Resolution, Congress turned its attention to The Committee of Five’s drafted statement of independence. The Committee met and wrote what became the Declaration of Independence between June 11-28. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, and Benjamin Franklin all served on the Committee, with Thomas Jefferson leading as the principle author. On July 2 the document was approved, and by July 4, 1776 Congress agreed on the final wording, thus leading to the official adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

The Committee of Five (National Archives and Records Administration: 532924 )

So, should we celebrate July 2 as our actual day of independence? It seems that John Adams thought so. He wrote to his wife Abigail:

“The second day of July 1776 will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Portrait of John Adams (National Archives and Records Administration: 50780435)

Adams's prediction of how Americans would celebrate this occasion was accurate, despite being off by two days. From the outset, Americans celebrated independence on July 4, the date shown on the much-publicized Declaration of Independence, rather than on July 2, the date the resolution of independence was approved in a closed session of Congress.

The signers of the Declaration of Independence were not all present on July 4, 1776, although Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin did write that they signed it the same day the document was approved and adopted. Other members of Congress, led by John Hancock, the President of the Congress, signed the Declaration nearly a month later on August 2.

The King of England viewed the members of the Second Continental Congress as traitors, rebelling against the crown. None of the signers were sentenced to death in response to their rebellious actions, but most were punished indirectly through the burning of their homes, imprisonment, or physical harm.

Oddly, both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, the only signers of the Declaration of Independence later to serve as Presidents of the United States, died on the same day: July 4, 1826, which was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration.

----

Sources:

Massachusetts Historical Society. Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776. Accessed July 2019. https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/popup?id=L17760703jasecond&page=L17760703jasecond_2

National Archives and Records Administration. Declaration of Independence. Docs Teach. Accessed July 2019. https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/the-declaration-of-independence

National Archives and Records Administration. Lee’s Resolution. Docs Teach. Accessed July 2019. https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/lee-resolution-independence

The Charlotte Baseball Club challenged amateur clubs from other cities to games in Charlotte and accepted challenges from other towns. The team’s poor performance one year prompted this sardonic boast in the May 13, 1892 Observer: “There are people who say it can beat the Pineville nine, that is, if Pineville has a nine.”

The Charlotte Baseball Club challenged amateur clubs from other cities to games in Charlotte and accepted challenges from other towns. The team’s poor performance one year prompted this sardonic boast in the May 13, 1892 Observer: “There are people who say it can beat the Pineville nine, that is, if Pineville has a nine.” team. J. H. Wearn (1861-1936) became

team. J. H. Wearn (1861-1936) became

erving the community as a librarian, through speed mentoring. The youth were also able to ask questions to panels of African American PhD students, UNCC undergrad students, participated in a tour of the campus and so much more.

erving the community as a librarian, through speed mentoring. The youth were also able to ask questions to panels of African American PhD students, UNCC undergrad students, participated in a tour of the campus and so much more. d this event was helpful and something they wish they could’ve experienced when they were younger.

d this event was helpful and something they wish they could’ve experienced when they were younger.

diversity and inclusion. As part of that mission, the Library started participating in the Pride Parade in 2018 by being one of the many groups to walk in the parade. Our group photo of that day gained the most likes on Instagram of all the library posts up to that point. During the parade, it was clear by the amount of people excitedly shouting, “It’s the library!” that our participation was important to our community.

diversity and inclusion. As part of that mission, the Library started participating in the Pride Parade in 2018 by being one of the many groups to walk in the parade. Our group photo of that day gained the most likes on Instagram of all the library posts up to that point. During the parade, it was clear by the amount of people excitedly shouting, “It’s the library!” that our participation was important to our community. This year, 25 staff members and their families from different library locations participated in the parade and represented the system by walking. One of the participants said, “I’m so glad I was able to participate. Seeing how supportive and appreciative the community was makes me glad the Library is involved. I can’t wait to participate next year!” Those who were not able to attend the parade aided in various way leading up to the event. Thank you to all who supported our efforts to bring Library resources to the Charlotte community and helping us build a stronger community!

This year, 25 staff members and their families from different library locations participated in the parade and represented the system by walking. One of the participants said, “I’m so glad I was able to participate. Seeing how supportive and appreciative the community was makes me glad the Library is involved. I can’t wait to participate next year!” Those who were not able to attend the parade aided in various way leading up to the event. Thank you to all who supported our efforts to bring Library resources to the Charlotte community and helping us build a stronger community!  significant gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer/questioning content, aimed at children and youth from birth to age 18.

significant gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer/questioning content, aimed at children and youth from birth to age 18.