The 1918 Spanish Flu: Is history repeating itself?

September 17, 2020

The Spanish Influenza ravaged the world just as World War I began to wind down, replacing deaths caused by other humans with deaths caused by disease. Despite what its name may suggest, the virus did not originate in Spain. Its origin was never pinpointed, but scientists believe it may have begun in Britain, France, China or the United States. Because Spain was neutral during the war, news was not censored (in countries that were participating in the war, news was censored as to not affect morale) and thus reporters were able to fully report on the virus and its effects, leading citizens of other countries to believe that Spain was ground-zero for the flu.

The virus’s initial symptoms included fatigue, headaches and scalp tenderness, followed by a loss of appetite, a dry cough, fever, excessive sweating and pneumonia if the disease was not treated. Worldwide, 500 million people became infected with the flu and at least 50 million people succumbed to the virus, with about 675,000 of those deaths coming from the United States.

Today, with COVID-19 sweeping the country and prompting stay-at-home orders and social distancing practices, significant parallels are noticeable between the response to the Spanish Flu and the response to this new virus.

Life in the Queen City

Newspapers served as the main source of communication for Charlotte’s 46,338 citizens during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic and largely impacted the attitudes surrounding quarantine. An article in the Charlotte Observer titled “Spanish ‘Flu’ Rapidly Spreads in Charlotte” described the city’s approach to quarantine as being resistant. A quote from the article read, “As the state health laws do not require a quarantine in cases of this disease, none will be attempted.”

Similarly, in an article reported by the Charlotte News and Evening Chronicle on September 23, 1918, the city health department superintendent Dr. C.C. Hudson remarked that he did not think “that quarantine would be necessary because of the ‘generalness’ of the disease and its ability to spread in spite of regulation, laws and health rules,” and that the influenza was “mild and will not hurt the victim unless complications develop.”

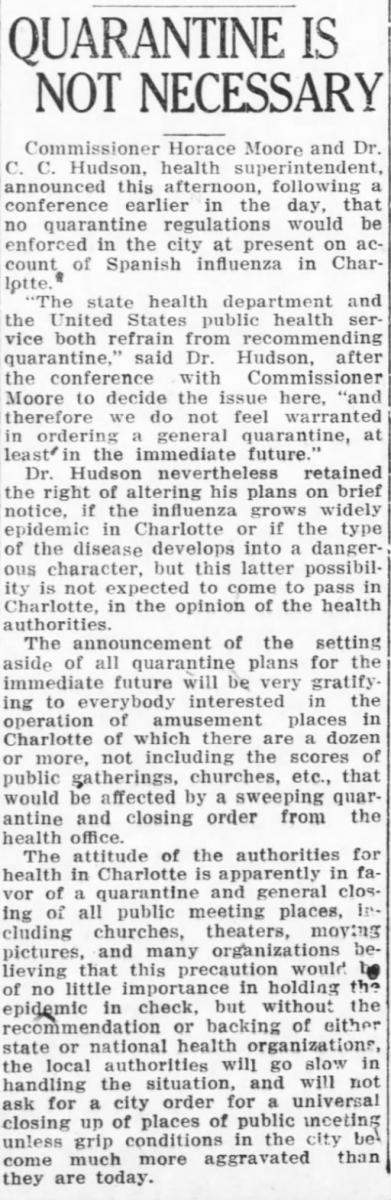

Charlotte’s resistance to quarantine continued into October, despite a quickly growing number of cases. The Charlotte News reported 50 confirmed cases in the city on October 2, which jumped to 175 on October 3. During this period, Dr. Hudson met with the Commissioner of Public Safety to discuss a possible quarantine, which resulted in an agreement that no quarantine was necessary. The justification given for this decision was that avoiding quarantine was very “gratifying to everybody interested in the operation of amusement places in Charlotte of which there are a dozen or more,” indicating that the superintendent and the commissioner had placed the interests of businesses over the interests of the public’s health, a trend that would become common in the city as the influenza raged on. The first official influenza death in the city was reported as being Rosa Stegall, who died on October 3.

Charlotte hesitantly put itself under quarantine on October 5, 1918. The City of Charlotte ordered theaters, schools, businesses, churches, and other “amusement places” to close to prevent the virus from spreading, as well as prohibited all indoor gatherings. After quarantine began at 6 o’clock on the evening of October 5, F.R. McNinch, the mayor of Charlotte in 1918, released a statement about the proclamation:

“We greatly regret the necessity for putting on a strict quarantine against public gathering and crowds indoors in the city, as we fully appreciate the loss in a commercial way and the great inconvenience to the people which such a quarantine means. (…) One of the most serious effects of the quarantine and one which gives us great concern is the serious interference with the plans of the liberty loan committee for public meetings… (...) Our liberty bond quota must be taken at all hazards, as we must not think only of protecting ourselves against disease, but it is our imperative duty to protect our army from both disease and death by providing the money necessary for the proper conduct of war. Let everybody buy at once just as many bonds as he possibly can and thereby help quarantine against the Hun [Germany].”

Once again, the city’s concerns rested not on the health of its citizens, but on commercial losses and liberty bond quotas. Liberty bonds were war bonds sold during World War I to support the Allied cause and were a way for citizens to essentially fund the war effort from their own pockets. McNinch’s focus on liberty bonds in his statement indicated that his priority was the city’s image, which later played a large role in the city’s handling of the outbreak.

South Tryon Street, Charlotte NC

Camp Greene

Camp Greene, a massive military facility constructed in 1917 in Charlotte to train Army soldiers for battle in World War I, began to see the rising number of influenza cases in the city and the city’s refusal to quarantine. Camp leaders had been closely watching the influenza’s spread across the east coast since its discovery, paying particular attention to the effects of the virus in other military camps. As a preventative measure, Camp Greene put itself under quarantine on October 3, 1918 in order to protect the soldiers in the camp from any exposure to flu cases in the city.

Section of Base Hospital at Camp Greene, c1918

Camp Greene released a statement about quarantine which read, “The quarantine regulations forbid any soldier to leave the camp or to enter the city except upon important business, and these cases will be few. Visits of civilians to the camp will also be discouraged.” The virus took hold of the camp swiftly. Death certificates in Mecklenburg County for males between the ages of 18 and 38, the ages of soldiers in the facility, show the first recorded flu death in this age bracket as being October 11, 1918. Despite their best efforts, within 2 weeks, the number of fatalities skyrocketed. Reports from the camp painted a grim picture of the influenza’s impact. So many soldiers had died of influenza that soldiers’ coffins kept at the camp’s railroad station were stacked from floor to ceiling.

Camp Greene funeral procession, c1918

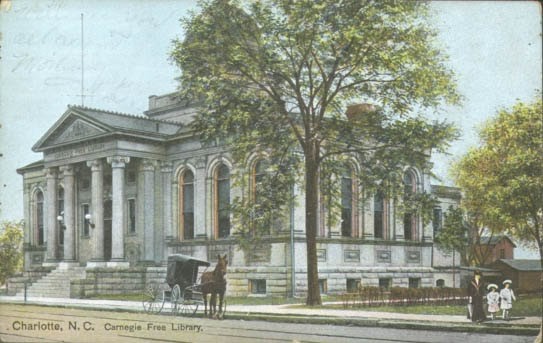

Several types of businesses in Charlotte were considered essential and were allowed to stay open, such as grocery stores and the Charlotte Public Library. Annie Pierce, the head librarian at the Charlotte Public Library in 1918, told the Charlotte Observer that the library would stay open every day throughout quarantine, with the exception of Sundays. Camp Greene’s quarantine measures prevented soldiers from coming into town for books and magazines, something they typically did on Sundays, so library staff decided that Sundays would be the best days for closure.

Carnegie Free Library, 1909

During COVID-19, the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library physically closed its doors on March 17, 2020 at 5 p.m. The Library remained closed for over two months before resuming limited services to the public on June 1. The Library continued to serve its community digitally, offering virtual programs, reference assistance and increased access to digital resources.

Productivity in Quarantine

Graduating class of Red Cross nurses, 1919

While schools were closed, city officials and reporters in Charlotte newspapers began to recommend ways for teachers and students to make themselves useful. One writer of the Charlotte News and Evening Chronicle reported that the city health department was calling for teachers who were “unemployed” due to the influenza outbreak to complete a census of Charlotte’s flu victims, asking teachers “to make a house to house canvas of the city and ascertain the number of people who are sick.” In addition, teachers were urged to volunteer as nurses at local hospitals. This report indicated that the insistence for teachers, in particular, to work on the frontlines was that they had “plenty of time on their hands” since schools were closed. These calls for teacher volunteers did not go unanswered, with at least five teachers from Charlotte reporting to volunteer as nurses at Presbyterian Hospital.

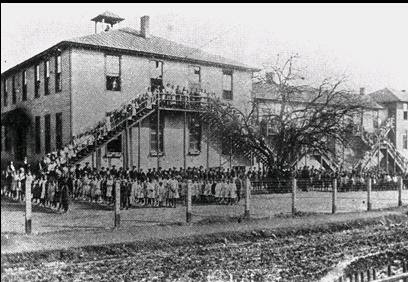

Myers Street School, c1940

Children were also targeted as possible helping hands during the crisis, with the “Junior Observer” column in the Charlotte Observer suggesting that idle school children report to local farms to help pick cotton. The columnist wrote, “It’s clean, pleasant work, and it appears to me that many of the pupils of the schools, both girls and boys, would be glad of the opportunity to keep busy, and at the same time earn quite a sum during this ‘vacation.’” The same column also took an aim at teachers, recommending that they accompany their students to the cotton fields. These suggestions came with no acknowledgement of health officials’ urging of the public to avoid gathering, however.

Voting

Political anxieties concerning elections plagued North Carolina politicians, who worried low voter turnout would harm their chances at being elected in the November 5, 1918 election. State officials had been urging citizens to avoid crowds and self-isolate for weeks, which exacerbated fears. To remedy the situation and encourage voters to turn up at the polls, the State Board of Health released a statement on November 1, 1918, urging eligible voters to vote despite its previous guidance to stay home. The Charlotte Observer summarized the Board’s statement in a report:

“The State Board of Health has advised the people of North Carolina that there is no need for staying away from the polls on account of influenza. It is set forth that this is a “crowd disease,” and no danger will be incurred in going out to vote. There should be no congregation of crowds around the polling places, and if the voters will go there, deposit their ballots and go their separate ways, the influenza will have no sort of a show to get in its work. One may go to the polls and cast his ballot with the same assurance of safety that he may go about any other errand. In giving out this advice, the State Board of Health has done a sensible thing, and one which is calculated to allay many of the silly fears that have swayed the people in recent weeks.”

This statement not only came after weeks of caution suggesting the opposite approach, but it also came a week after 2,410 North Carolinians had succumbed to the virus, many coming from Charlotte.

Controversial Decisions

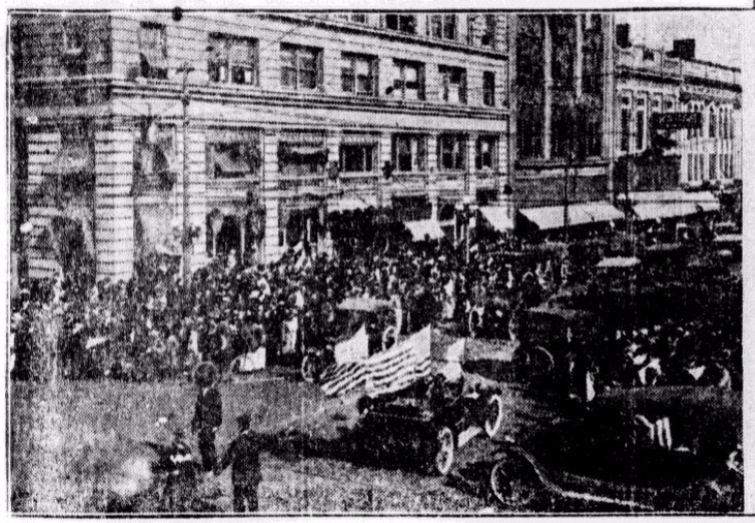

Crowds in the street on Armistice Day, November 1918

Beginning in late October, city leaders, namely Mayor McNinch and prominent health officials, began calling for a lift of the quarantine, citing concerns about businesses and economic losses. The quarantine was lifted on November 11 on Armistice Day, the official end of World War I, which led to celebrations with massive crowds despite the influenza outbreak showing no signs of slowing. Shortly afterward, the virus roared back into the city, leading to hundreds more deaths and a second wave of quarantines in schools. Businesses and “amusement places” remained open because it was “easier to overcome the liabilities of a quarantine in this sphere [school] than in any other,” indicating that businesses were so strongly opposed to another city-wide quarantine that city officials believed one would significantly damage their political standings.

According to official reports, only 800 Charlotteans (about 1% of the city’s population) succumbed to the virus, which was attributed to city officials’ swift action to curb infection rates. Compared to the rest of the state, which suffered 13,000 deaths, Charlotte appeared incredibly fortunate. However, we may never know how many Charlotteans actually died as a result of the virus. According to a recent Charlotte Observer article, death certificates show that city leaders underreported the total number of fatalities by half. During the height of the pandemic, when Charlotteans were dying at a rate of 10 per week, leaders underreported fatalities by two-thirds. Because fatality numbers had been underreported to the public, McNinch and other city leaders were successfully able to convince the city that the virus was under control and no longer a danger to the citizenry, leading to the early lift of quarantine, which caused more deaths that also went underreported.

Now, more than ever, it is important to look to the past and learn from its mistakes. In 1918, Charlotte city leaders put profits and image above the health of its citizens. In 2020, it is imperative we stay vigilant to prevent a pandemic from happening again, or at the very least understand how to mitigate the socio-economic and health effects on our community.

History may have a habit of repeating itself, but it’s up to us to decide whether the bad or the good is what’s repeated.

--

This blog was written by Taylor Marks of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte (UNCC).

Sources:

Belton, Tom. “WWI: North Carolina and Influenza.” NCPedia. (Accessed April 2020) https://www.ncpedia.org/north-carolina-and-influenza

Cockrell, David L. ""A Blessing in Disguise": The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and North Carolina's Medical and Public Health Communities." The North Carolina Historical Review 73, no. 3 (1996): 309-27. Accessed May 15, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/23521395.

Lauren A. Austin, “‘Afraid to Breathe’: Understanding North Carolina’s Experience of the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic at the State, Local, and Individual Levels” (ProQuest LLC 2018).

McKown, Harry. "October 1918 -- North Carolina and the 'Blue Death'," NCPedia. October 2008. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/north-carolina-and-blue

Mecia, Tony. “Charlotte’s other big pandemic.” Charlotte Ledger Business Journal. April 11, 2020. (Accessed April 2020) https://charlotteledger.substack.com/p/charlottes-other-big-pandemic

Steinmetz, Jesse. “Charlotte Talks: This Is Not Our First Pandemic.” WFAE 90.7. April 21, 2020. (Accessed April 2020). https://www.wfae.org/post/charlotte-talks-not-our-first-pandemic#stream/0

Washburn, Mark. “THE BIG LIE: 102 years ago, Charlotte leaders downplayed devastation of Spanish flu.” The Charlotte Observer. April 12, 2020. (Accessed April 2020) https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article241812591.html?fbclid=IwAR3YnVu2Edy-fMaMdgxyOD68dsEZgW-eiWY5LfGBNs9AGu7JLWyVJR_BLI0