Behind the Vault Doors: Harry Patrick Harding Papers, 1917-1962

October 29, 2020

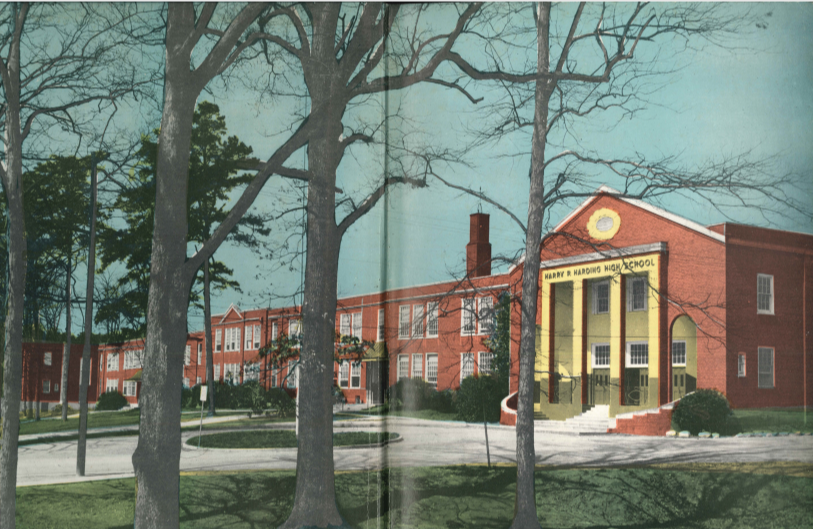

In 1935, Harding High School opened on Irwin Avenue. Its namesake was strongly against the use of his name, as he believed school buildings should not be named for living superintendents. However, the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) prevailed, and the school was named to honor Harry Patrick Harding (1874-1959) who served as the Charlotte School Superintendent from 1913-1949.

The building remained a high school until 1961, when the Irwin Avenue building was designated a junior high school. The high school was moved to Alleghany Street, and was named Harding University High School the same year. The Irwin Avenue building later became an elementary school, and finally a Head Start Center. By the late 1980s, the building was demolished, except for the auditorium and gymnasium, and another structure was built to accommodate the Irwin Avenue Open Elementary School.

Harry Patrick Harding, 1940

Born in Aurora, North Carolina, on August 14, 1874 to Confederate Army Major Henry H. and Susan Elizabeth Sugg Harding, Harry Patrick Harding was known for most of his life as “Harry” or “H.P.” He was one of eight children, although two died in infancy. Major Harding was a farmer and a delegate to the state House of Representatives during Harry’s early years. In 1885, the family moved to Greenville, where Major Harding became a teacher, and eventually spent four years as superintendent of the schools. Harry was educated at Greenville Male Academy and the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, where he graduated in 1899. In 1931, he received his Master of Arts degree from Columbia University, and an honorary doctorate from Davidson College in 1951.

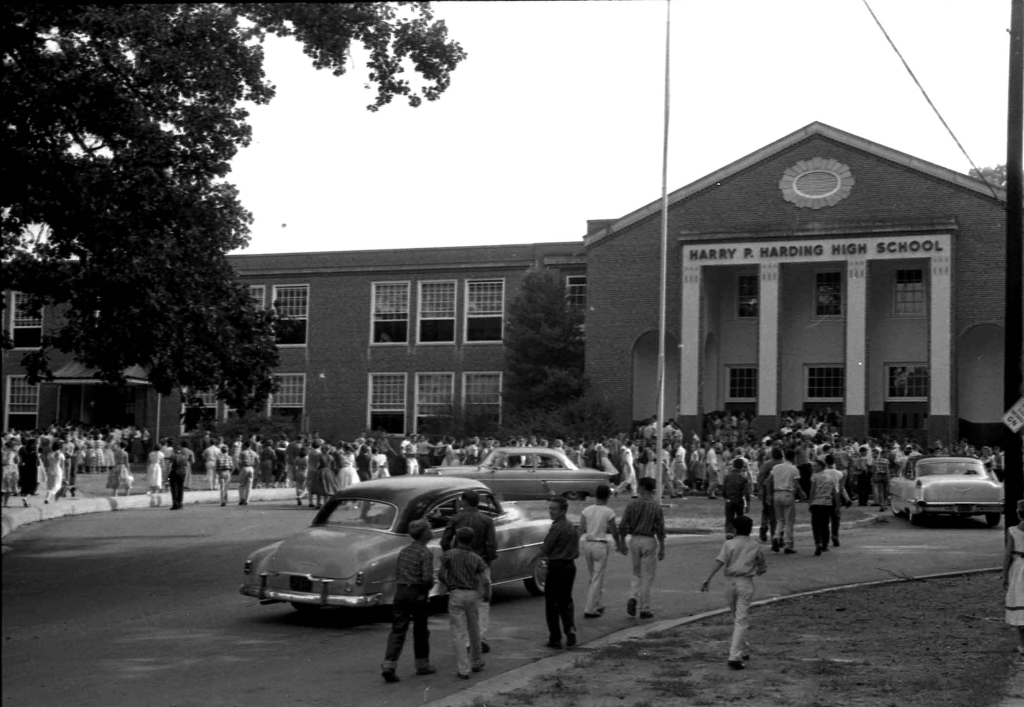

Courtesy of The Charlotte Observer, c1957

After graduating from UNC, Harding became principal of New Bern High School. He left to organize the Oxford schools in 1901, but returned to New Bern as superintendent in 1902, and remained for two years. Then in 1904, Alexander Graham, superintendent of the Charlotte school system, recruited Harding to become principal of one of the graded schools. In 1912, Harding was appointed assistant superintendent, a position he held until succeeding Graham as superintendent the following year. Harding stayed in this position for 26 years, retiring in 1949. Following his retirement, he continued to maintain an office and visited schools as superintendent emeritus.

Harding made great changes to the Charlotte school system during his tenure. He cared deeply about the students under his charge and was more interested in building the character and personality of a child, than teaching hard facts. Some of the strides Harding involved himself in included streamlining teaching in the high school by having teachers specialize in one subject; overseeing the first junior high school in North Carolina in 1923; adding elective courses to the curriculum to encourage and interest students in completing their educations; and persuading voters to approve special taxes and bonds in order to build better schools, supplement teachers’ salaries, and improve children's health. One of Harding’s most difficult challenges came in 1933-1934, when the state legislature annulled the charters that allowed cities to levy special taxes for the schools, which created huge deficits in the budget, loss of teachers, and reduction in instruction time. Harding was eventually able to get voters back on board in 1935, after approaching local businessmen to obtain their support.

Dorothy Counts-Scoggins, first black student at Harding High School, 1957

Despite the many positive contributions Harding made to CMS, he led a segregated system. CMS was segregated until 1957, when Dorothy Counts became the first black student to attend the all-white Harding High School. CMS largely continued to be segregated even after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in May 1954. Until 1957, no black students attempted to attend an all-white school. Delores Huntley (one year at Alexander Graham Junior High), Girvaud Roberts (two years at Piedmont Junior High), Gus Roberts (graduated from Central High School in 1959), and Dorothy Counts (one year at Harding High School) all changed that in 1957 when they decided to enroll at white schools.

By 1964, CMS had 88 segregated schools (57 white, 31 black), which ultimately led to one of the most significant court cases in our region’s history—Swann v. the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. After many years of rulings, in 1970 Federal Judge James B. McManus ruled the CMS was not desegregated and demanded total integration.

Harding High School, The Acorn, 1957

In addition to his work as superintendent, Harding also served as a trustee of UNC, and was president of the North Carolina Association of City School Superintendents, of the South Piedmont Teachers Association, and of the North Carolina Education Association. He spent two summers teaching at UNC, served on the North Carolina High School Textbook Commission, and was a member of the Ninety-Six Club, which consisted of two superintendents from each state. Locally, he was a member of the Rotary Club, the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce, and the Executives Club.

In his private life, Harding was a husband and father. He married Lucia Ella Ives (1876-1963) of New Bern in 1903. They had two children, Lucia Elizabeth (1908-1987), and a son, Harry P. Harding (1910-1911), who died in 1911 of ileocolitis, today known as Crohn’s disease, at just over a year old. The remaining five of Harding’s seven siblings held estimable positions as well. William Frederick Harding lived in Charlotte and was a Superior Court Judge, Fordyce C. Harding was a lawyer serving in the North Carolina Senate from 1915-1920, Jarvis B. Harding built roads in Mexico as a civil engineer, and their sisters, Sudie Harding Latham and Mary Elizabeth Harding, were teachers.

Harry P. Harding died on July 13, 1959 of hypertensive cardiovascular disease. He is buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Charlotte, North Carolina.

The Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room houses the Harry P. Harding Papers (1917-1962), which are only available for virtual research due to the COVID-19 crisis. Contact the Carolina Room’s Archivist for more information on how to access this collection: (704) 416-0150 or [email protected].