How a suffrage parade float attracted so much attention

August 11, 2020

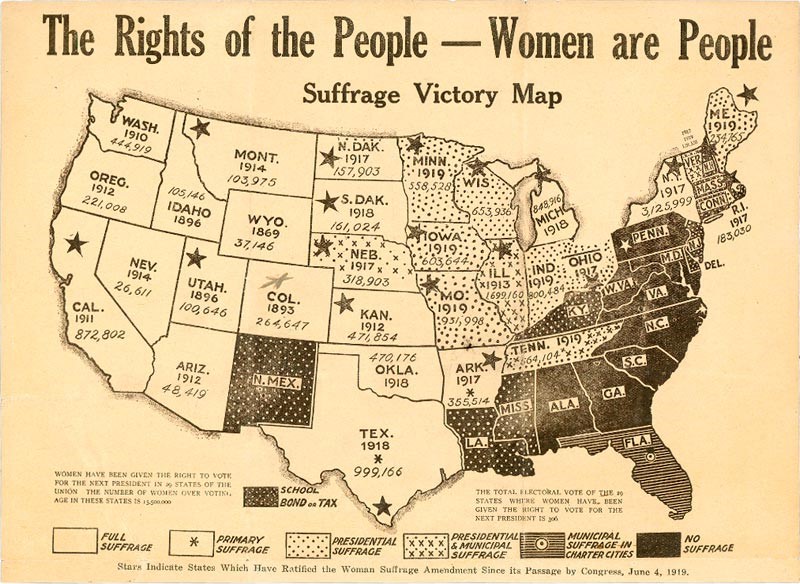

This month, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library celebrates the centennial of the 19th Amendment. This amendment to the United States Constitution added the declaration that no state could deny a citizen the right to vote "on account of sex.” Many states already allowed limited voting rights for women by 1920, although North Carolina, along with nine other states, still restricted all elections to men only. (See map.) It took this amendment to make women’s suffrage universal throughout the nation.

A suffragist map from late 1919 showing the extent of voting rights for women and the progress of ratification of the 19th Amendment by state legislatures.

The movement to win the right to vote for women was decades in the making, but it garnered very little public support in North Carolina until 1913 when a state chapter of the Equal Suffrage League opened. A few days prior to the yearly Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence Day parade on May 20 (a day of local patriotism much-celebrated once in Charlotte), local chapter members decided they would participate. They hired a driver with a horse-drawn cart, decorated it, and set out along the parade route.

Suzanne Bynum, Anna Forbes Liddell, Catherine McLaughlin, Jane Stillman, Julia McNinch, Bessie Mae Simmonds, and Mary Belle Palmer stand up for women’s suffrage. Charlotte, NC, May 20, 1914. Courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

“A success? I should say so!” said the male writer of an article for the Charlotte Observer. “The suffragist cause thrives on publicity, and [the float] was one of the features of a crowded day. Thousands who had ignored the subject discussed it that night.” -Victor L. Stephenson, “Story of that Suffrage Float,” The Charlotte Observer, (November 1, 1914).

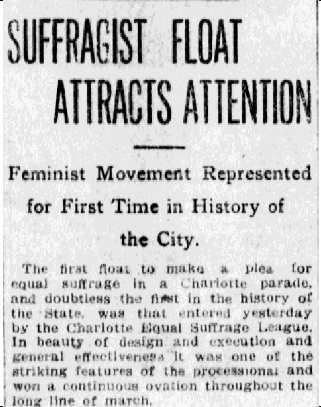

Article in the Charlotte News, May 21, 1914

Later that same year, the Charlotte chapter hosted the statewide convention of the Equal Suffrage League in November. The event attracted luminaries from around the state and received special attention from The Charlotte Observer, which published a special edition to cover events at the convention. Attendees planned to lobby hard for women’s suffrage in the state, or, as The Charlotte Observer put it, “lay siege to the next legislature.”

The year 1915 began with high hopes that were quickly dashed. In February, both the State House and Senate of North Carolina declined – by large majorities - to amend the state constitution to allow votes for women. In the next four years, as other states embraced equal suffrage, North Carolina did not join the movement. When the 19th Amendment was finally adopted by the United States Senate in 1919, both North Carolina Senators voted against it.

The drama then shifted to state legislatures. Thirty-six of the forty-eight states needed to say "yes" for the amendment to be ratified. By August 1920, 35 states had done so. The General Assembly of North Carolina was called into special session to consider it, and local suffragists hoped to claim the honor of putting the amendment over the top for their state. On August 18, however, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify. The North Carolina House held a vote on the amendment anyway the next day and voted it down in a purely symbolic gesture.

Alas, this expansion of the right to vote did not improve access to the polls for African Americans in North Carolina. State laws that effectively barred African Americans from participating in elections remained in place so that Black women remained as excluded as before ratification. The editor of the Star of Zion, a Black newspaper in Charlotte, pointed to the irony of celebrating a partial expansion of rights that should belong to all. He referred to the 19th Amendment as the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment,” after the woman who had proposed it in 1875.

“The name of the 19th Amendment savors of universal freedom. Susan B. Anthony herself was as ardent an abolitionist as she was a suffragist, and her amendment presupposes that all citizens in free America should have the use of the ballot. And if she were living, she would keep up the fight for it.” (Star of Zion, August 26, 1920).

In this election year, the Library is partnering with the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) offering programs like this one to encourage everyone to look back at past accomplishments and to move forward with empowerment to make a difference in one's own community. To learn more about Engage 2020, click here.

--

This blog was written by Tom Cole of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room at Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Molloy, Jill. “Timeline of Women’s Suffrage,” NCPedia, published by the North Carolina Government and Heritage Library, accessed July 22, 2020. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/timeline-womens-suffrage